On 15 November 2022, the European Studies Centre, in cooperation with SEESOX, hosted an event marking the centenary of the conclusion of the Greek-Turkish War in Asia Minor. Titled Globalizing the Greek-Turkish 1922: displacements, population movements and the coming of the national state, the discussion was chaired by Faisal Devji (St Antony’s College). The speakers were Georgios Giannakopoulos (City University, London), (University of Leeds), and Marilena Anastasopoulou (Pembroke College, Oxford).

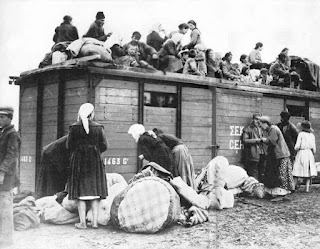

Giannakopoulos’ presentation focussed on the population exchanges between Greece and Turkey in the aftermath of the Greek-Turkish War. His guiding question was whether the Greek expansionist project was an effort to protect Greek populations, or an imperialist venture. The motivations behind the post-war settlement were a “unique blend” of imperialist, nationalist, and internationalist imageries, with various figures representing different faces of the endeavour: Nansen as the humanitarian, Curzon as the imperialist, and Venizelos as the nationalist.

At the same time, he situated the developments in Greece and Turkey within a broader international context. The “Global 1922,” he pointed out, included a number of state-forming events, such as Egypt’s declaration of independence, the creation of an Irish Free State, and the official establishment of the USSR. The infamous March on Rome also happened in the same year. According to Western commentators like Toynbee, disquiet in Asia Minor threatened the West with a new kind of “Moral Balkanisation.” However, the presenter argued that this global perspective challenges myths of Western homogeneity.

Giannakopoulos concluded that the Treaty of Lausanne was not a departure from previous treaties but the logical conclusion of the politics of territoriality. Lausanne, he said, proposed 19th century solutions to 20th century problems, but would simultaneously become a template for resolving minority issues in the future. As Frank would detail in his presentation, authoritarian countries such as Germany, Italy, and the USSR drew inspiration from Greece and Turkey, though they did not study Lausanne closely as a legal precedent.Frank began his presentation by discussing the complete change in atmosphere that led to the treaty’s signing. The idea Nansen had championed of a population exchange had seemed dead in the water but, in just over two months, an agreement had been reached. Its journey from a distant prospect to its enshrinement at Lausanne could be attributed to the fact that all parties saw advantages in securing a deal. Furthermore, it was hard to get agreement on anything else. Nevertheless, the Treaty of Lausanne met with criticism from all sides, with Curzon declaring he “detested having anything to do with it.”

The focus of Frank’s presentation was on how the assessment of Lausanne shifted over the 1920s from condemnation through admiration to emulation. This shift was occasioned by three considerations. Firstly, Greece and Turkey achieved radical transformation following the resettlement. Both of the states consolidated their territory and pursued their own paths towards modernisation. The League of Nations was heavily involved in the modernisation of Greece, while Turkey impressed the Western world with its transformation into a modern secular state and “civilised power”.

This led to a second development: diplomatic transformation. Following the return of Venizelos to power, Greece and Turkey signed the Ankara Agreements, which confirmed the completion of resettlement by liquidating the commission responsible for its implementation. The détente between these two countries led to the 1933 Treaty of Friendship and the signing of the Balkan Entente in 1934, and enabled Turkey to join the League of Nations. Finally, Turkey’s and Greece’s transformation stood in marked contrast to growing concerns over minorities in the rest of Europe. The Near East began to be held up as a success story in the context of turmoil in the rest of Europe and, indeed, the most egregious abuses of minority rights happened in countries not covered by the League’s minority protections, such as Italy.

Finally, Anastasopoulou presented her research on Asia Minor refugee memory in Greece. Her guiding questions were: how have memories of the 1922-24 forced displacement changed over time from one generation to the next? And how do people with these memories and identities think about subsequent migration?

She argued that memory identity is constructed, shaped, and reshaped, passing through different stages of trauma across generations: from silence to latency, and ultimately to reawakening. As for how 1922-24 refugees and their descendants view subsequent migration, the presenter uncovered a number of noteworthy trends. Firstly, people tend to construct hierarchies of acceptability based on binary distinctions, such as the perceived difference between “migrants” and “refugees”. Furthermore, shared characteristics like religion play a key role in the rejection or acceptance of migrants. The problem is also complicated by volatility and contradictions, with numerous respondents holding conflicting feelings.

Anastasopoulou noted that reactions to subsequent migration have a geographical component. The inhabitants of Lesvos are traditional gate-openers, while Central Macedonians act as gatekeepers, and Athenians tend to hold more pragmatic views. Coupled with this geographical distinction are generational differences: while modern refugees prompt historical reflections on the side of the first generation of migrants, the fourth generation is more forward-looking.

Opening the question-and-answer session, Devji shared his own expertise regarding South Asia, pointing out the paradox of heterogeneous empires like the UK encouraging homogeneity within the Middle East. As Frank had noted, the British simply had no interest in minority protection, with their own model favouring political and cultural assimilation over separation. He also brought up the plurality of models that could have served as an alternative to Lausanne: many Muslim commentators, for example, distrusted nation states, and some saw the USSR as representing a non-nationalist alternative to how a state could be constituted.

Responding to Anastasopoulou, Devji raised the question of terminology. Lausanne had set a rhetorical precedent for the partition of India, but the UN refused to recognise the resettled populations as being “refugees,” as they had countries to receive them. However, the UK in the 1970s had applied the term “refugees” to the East African Asians, even though they had British passports. Anastasopoulou responded that the term “refugee” is, similarly, not strictly correct when speaking about the Greeks and Turks who were moved in the aftermath of Lausanne. Nevertheless, members and descendants of these resettled populations do identify with a positive refugee identity. Especially when speaking about modern migrants, the inhabitants of Lesvos, for example, position themselves as “refugees” regardless of their generational removal.

Questions from the audience included one about the possibility of what Curzon referred to as a “benevolent unmixing” of populations, either through secession, segregation, or separation. Frank responded that one successful example was the Velvet Divorce of Czechoslovakia, while Giannakopoulos floated the idea of federalism. Another asked why the “national tragedy” of what the Greeks saw as the loss of Asia Minor was so keenly remembered. Anastasopoulou ascribed this to generational shifts: memory is dynamic, and what had once been a silent memory of trauma was re-awakened during Greece’s 1974 democratisation.

One questioner challenged Giannakopoulos’ claim that Lausanne was a 19th century solution, drawing attention to the novelty of the “unmixing” idea which would come to inspire 20th century figures like Hitler. Frank agreed with this assessment, adding that Lausanne was in effect the first revision of the Treaty of Versailles, foreshadowing the Munich Conference. Its initial condemnation stemmed from a break with 19th century ideals of individual and property rights. Giannakopoulos accepted that Lausanne was revisionary but asserted it still “digested” older moments. Minorities began to be treated as a political problem since the 1870s, and the toolkit for resolving these problems had been inherited from that time.

Another questioner said he was struck by contrasting attitudes among the resettled Greeks, asking what determines the tendency to feel empathy as opposed to rejection. Anastasopoulou answered that for one, geography matters: populations that style themselves as “guardians of the borders” are more convinced of Greek homogeneity and tend to be more hostile. Other variables include generational status, religion, culture, language, and memories of trauma, all of which construct a community of values. Those who do not share at least part of this identity invariably become an “other.” Often, the discourse does not simply oscillate between acceptance and rejection, but involves competitive victimisation as settled populations try to safeguard their position in society.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.