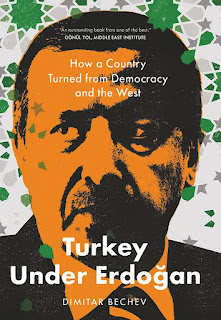

SEESOX held its last hybrid event of the Hilary 2022 Term, taking its title from, and focusing on, Dimitar Bechev’s latest book. The event was chaired by Ezgi Başaran (St Antony’s College, Oxford) who introduced the book as a tour-de-force of events and critical junctures in the past two decades in Turkey, as the country succumbed to authoritarianism and nationalism, and as it further distanced itself from the West. The author and speaker Dimitar Bechev (Oxford School of Global and Area Studies (OSGA)) was accompanied by the discussants Mehmet Karlı (St Antony’s College, Oxford) and Kerem Öktem (Ca’ Foscari University of Venice).

Bechev began by commenting on Turkey’s role as a critical player in the war in Ukraine. The Turkish government is currently stuck in the middle, given the tremendous economic challenges it is facing, the pressure from a united opposition, the discontent brewing among the Turkish society, and now a geopolitical crisis in its neighbourhood where it has robust connections to both parties.

He then zoomed back from the current situation to talk about the evolution of Turkish foreign policy since the end of the Cold War. Turkey had reinvented itself from being an EU-applicant to a central player with connections throughout the Middle East, the Balkans and the Black Sea. Turkey had been very confident that it could shape its neighbourhood and its image, bringing together Islam, democratic experience, economic growth and a populist leadership style, until it discovered its limitations and faced a pushback. Despite the lessons learnt, Turkey still wants to influence its environment and to play a central role in the balance between the West, Russia and China. Turkey’s process of becoming an ambitious regional player as a result of domestic politics, geopolitics, and ideology, is one of the major themes in the book. Another important theme in the book is the Turkish effort to democratize and the depressing story of de-democratization. Bechev reminded the audience of Erdoğan’s speech at St John’s College in 2004, where he talked about his ambitions to be an EU member state, efforts to resolve historic issues such as the Kurdish question and military interference in politics, and to strengthen Turkey’s democracy. Almost 20 years later, we are far from these aims, and for the past decade there has been a rigorous conversation in Turkey as to who is to blame. Did Erdoğan have a master plan in 2002 to hijack Turkey’s process of Europeanization and democratization and to install his own rule, or was it a story of contingency as a result of choices made along the way? Positioning himself on the latter side of the debate, Bechev pointed to several explanations as to why such a turn took place: 1) Erdoğan’s ambitious personality and willingness to stay in power, 2) The political structure in Turkey, with a polarized domestic political scene, a ‘winner takes it all mentality’ and a lack of checks and balances, 3) The EU capitalizing on this coalition of various forces, pushing for a change in Turkey through AKP’s wide range of followers, and 4) The role of nationalism and Erdoğan re-fashioning the idea of a strong state dominating society, even picking and using aspects of Kemalism in a way that suits his interests.

Bechev ended his talk by highlighting the strengthening of the opposition as we approach the 2023 elections. He emphasized Turkey’s long history of democratic experience and pointed to parallels with Latin democracies that moved back and forth from democratic politics to forms of authoritarianism. He stated that the EU can still play a role in Turkey’s democratization as the Turkish economy is deeply embedded in the EU’s economy.

Karlı pointed to the book’s skilfulness in describing the developments in Turkey’s foreign policy in a historical continuum. He then commented on the master plan vs. contingency debate by highlighting Erdoğan’s instincts to consolidate his power as the main motivator of his choices. He also talked about the changes to the legal system adopted during the first five years of AKP’s rule as well as the gap in the literature on the Gülenist movement. Öktem gave his personal reflections on the book, praising its sober tone and ability to weave a complex narrative of domestic and foreign policy aspects in an easily readable format. He then raised the question of what would be left of Erdoğan and what would constitute Erdoğanism in a post-Erdoğan era. Dimitar Bechev agreed with Karlı on the role of Erdoğan’s ambitious personality, and added that Erdoğan departed from the initial triumvirate organization of the AKP with Abdullah Gül and Bülent Arınç, during the Gezi protests, and established his own personalistic regime as early as 2014. He responded to Öktem’s question by stating that we can think of Erdoğanism as a symbolic legacy; in twenty years’ time it is likely that there will be a segment of the electorates using Erdoğan as a political symbol, referring to him as a ‘leader who made Turkey great’ or ‘your common man’s politician’. He added that some of the institutions he introduced might also linger on, despite the opposition’s promises to reinforce the parliamentary system.

In the Q&A session a range of issues was explored, including the role of religion in securing the loyalty of Erdoğan’s electoral base, the conceptualization of democracy in the book, Turkey’s relations with Iran, and the impact of high inflation on Erdoğan’s survival prospects.

Aslı Töre (St Antony’s College, Oxford)

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.